Dialogue in the Dark

We all become phantoms, phantoms of ourselves, ghosts reappearing as fragments

As a librarian, I spent a lot of time in special collections: studying literary manuscripts for handwritten changes by the author, and reading correspondences between an author and others. (None of that was part of my formal job as a librarian, but I have a lot of curiosity and found time outside regular work to find my way into the special collections reading room and, occasionally, the vault.) Manuscripts are valuable resources for literary scholars who study the writing process and how an author revises a work.

Our memory fools us

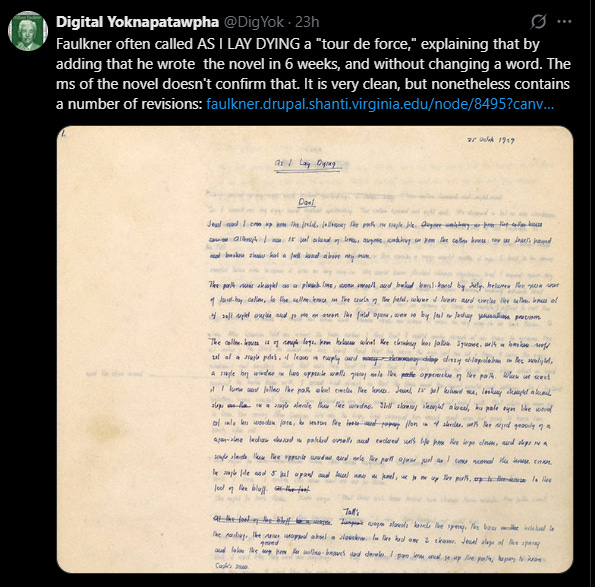

If you’ve read much Faulkner, you’ll know that he writes a lot about the mistrustful nature of memory. Evidently, his own memory of writing As I Lay Dying was not as faithful as he remembered, or he strove to create a mystique about the inspiration that poured out of him by claiming that “he wrote the novel in 6 weeks, and without changing word.” The Digital Yoknapatawpha project at The University of Virginia details that claim as not entirely true.

Faulkner did change some words but not nearly to the extent that other writers revise their first drafts. But, hey, he’s Faulkner.

As writers increasingly co-author and/or edit with AI, how much will we know about an author’s writing process in the future?

Let’s set aside the argument of whether writers should or should use the aid of AI. And let’s not compare anyone to Faulkner. I use this example by Faulkner because it came across my X feed the day that I was thinking about this topic.

Even without the use of AI, the process of literary analysis based on manuscript collections has been impacted by handwritten (or hand edited) drafts replaced by word processors and written correspondences replaced by email. A lot of literary history has been lost in the last few decades, though there are researchers working on archiving digital files and versions.

Lots of writings are toss away works. John Lennon referred to many of his songs as throwaways: songs that were crafted quickly or without significant emotional depth. In the 1980 Playboy interview with David Sheff, Lennon goes through the catalogue of Beatles songs and his own while describing many as “throwaways”; I was disappointed that one of my favorite Lennon solo numbers was described that way. Maybe he was simply being self-deprecating.

But a true example of a throwaway work where we don’t need a historical analysis would be Ballard, an adaptation by Amazon of the Michael Connelly novels featuring his female detective Renée Ballard.

Last night, I was bored. I had finished watching Squid Game, season 3, the night before and wanted another series. I had the feeling that Ballard wouldn’t be good since it was a spinoff of the Bosch series, which started out good but I gave up on watching eventually. I got halfway through the first episode of Ballard and decided that I was wasting my life by watching it. I was a fan of Connelly’s Bosch novels, particularly the early ones but never cared for the Ballard series. I’ve stopped reading Connelly because I couldn’t remember which novels I’ve read before. Likewise, I’ve given up on watching the Mission Impossible movies because they all seem the same, and I can’t remember which ones I’ve watched. Sometimes I like mindless entertainment as a brain break from my Criterion Collection.

Despite what Hollywood writers say, a lot of the stuff on streaming could be written by AI, or made better with the aid of AI.

AI Filmmaking is here. Runway has a lot of momentum. Some incredible independent films will be made with AI. (More bad films will be made with AI.)

But here’s where things get interesting. AI doesn’t have to be a shortcut for cranking out slop to fill streaming channels, but a tool for building a new kind of narrative experience altogether.

Generative AI starts to shine not by replacing writers or directors, but by enabling entirely new kinds of stories that unfold through interaction, exploration, and presence.

If you follow my work, you know I’m interested in branching narratives and narrative-driven games.

Branching narratives: stories with multiple possible paths and outcomes.

Branching narratives are an area where AI brings something to the table that isn’t nearly as possible with humans writing out and filming every possibility.

Interactive narrative design

That brings me to Never Fear Paris, an interactive historical mystery I've been developing for the past year. Set in 1920s Paris, the story begins in a smoky nightclub with a surrealist dancer named Elodie and an artist named Marcel. You play as a character who steps into the story as a photographer, an observer of human nature, who witnesses something strange, maybe even sinister, and becomes entangled in a mystery that unfolds across the city.

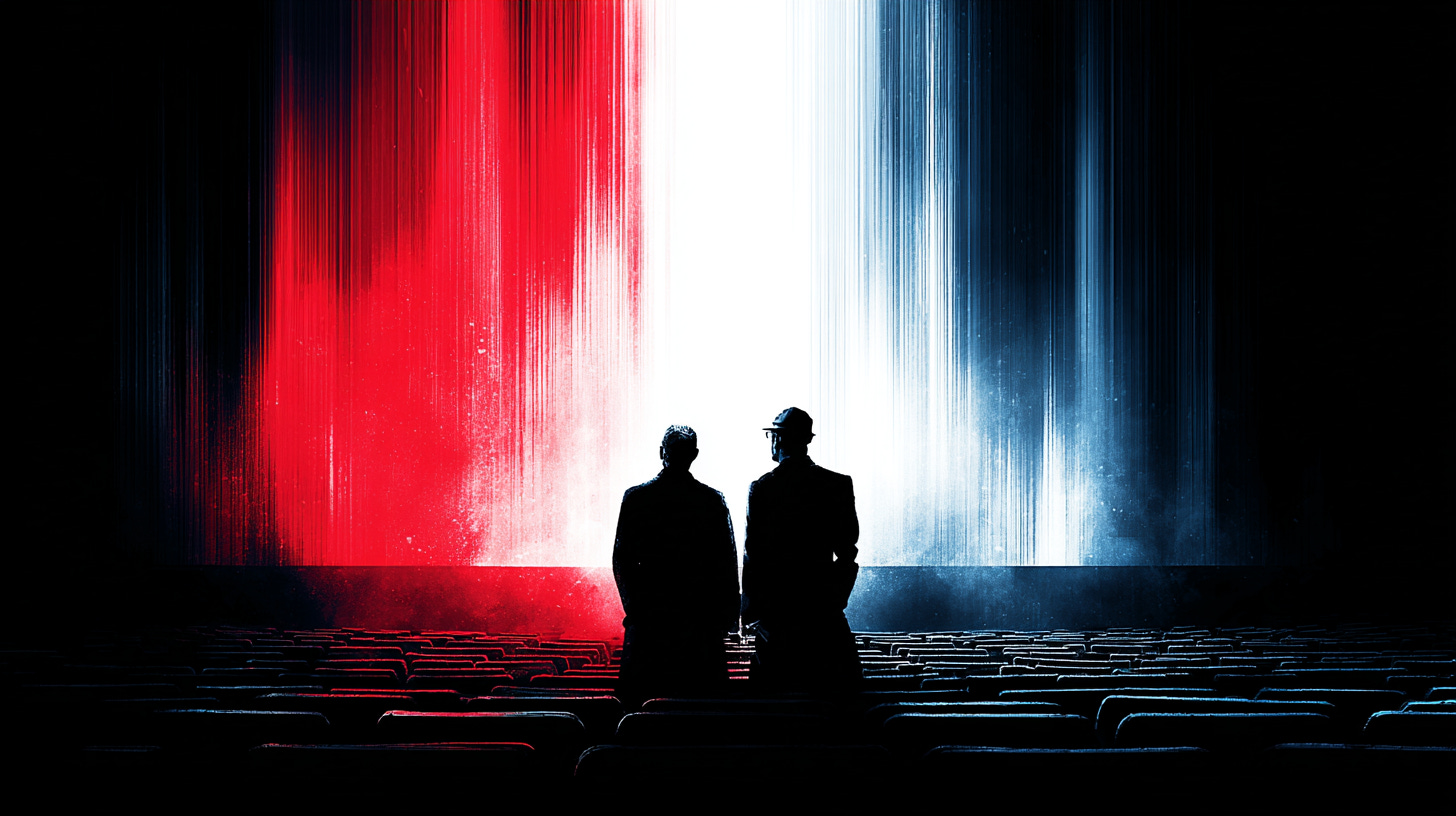

Dialogue in the Dark, which you’ll find below, is a preface to that story told from today’s perspective. It’s a conversation between an archivist and a filmmaker, spoken over still images and archival footage. In the interactive version of the story, this dialogue becomes the root of a branching narrative where players can pursue multiple paths, make choices, and uncover different truths depending on their perspective and decisions.

The script for Dialogue in the Dark is designed to serve as a foundation for future interactivity, where AI will dynamically generate variations, continuations, and responses as players push deeper into the story world.

For the most part, I consider Dialogue in the Dark to be a throwaway (to use Lennon’s phrase). The larger vision I’m pursuing is Never Fear Paris, whereas I consider this Dialogue to be a slice of that larger work, a possible entry point.

It’s a throwaway also in the sense that this prelude isn’t needed for the full Never Fear Paris experience. This dialogue will serve as a testbed for generating branching narratives with AI.

Script: Dialogue in the Dark

[I’m leaving out the visual descriptions of the scene.]

Filmmaker: An empty chair in a room full of dreams and a canvas holding unfinished thoughts. Everything vanishes.

Archivist: Ah, the empty studio. A space filled with more questions than answers, as if he stepped entirely out of reality. The last place Matteo Monti was seen. You know, the art scene back then was like jazz filled with ideas and conversations.

Filmmaker: A perfect setting, and yet he left all that.

Archivist: Left? vanished? I've always thought something more sinister was behind his disappearance.

Filmmaker: This headline, it's haunting.

Archivist: Many. Some thought it was a publicity stunt. Others believed he got lost in his surreal world. Others think he simply boarded a boat back to Buenos Aires. But there's no trace of him in Argentina. I've spent years in Buenos Aires trying to find anything about him. I did find these letters he wrote from Paris to his former mentor, but they're all dated before his disappearance. These letters offer a glimpse into his mind. He often spoke of blending reality and dreams.

Filmmaker: Could his disappearance be his ultimate masterpiece?

Archivist: More intriguing are these scraps of paper found in the nightclub.

Filmmaker: Wait, what are these?

Archivist: Evidently, they’re thoughts Monti would scribble on scraps of papers at the club and then toss aside. He did that night after night until he vanished. His friend Marcel secretly collected these scraps and kept them. I think, at first, Marcel was seeking insight into Monti's creativity. Marcel was seeking insight into Monti's creativity. Then, after the disappearance, Marcel became obsessed and a bit of a detective.

Filmmaker: Yes, Marcel, I know about him.

Archivist: Then, you know...

Filmmaker: That they were lovers and enemies?

Archivist: Competitors. Everybody in that scene were lovers and enemies, competing in life, love and art.

Filmmaker: This unfinished painting, it's like an open-ended question.

Archivist: Or a clue, some say he disappeared to complete it in solitude.

Filmmaker: What happened to the painting?

Archivist: It turned up years later in a catalogue from an art gallery. Though some scholars believe it was not finished by Monti. The provenance is unclear. It got sold to a private collector who eventually got tired of people coming around asking about it. I have the collector's name here somewhere, but he started refusing all requests to see the painting or even talk about it. I've heard he even rejected some big offers to buy it.

Filmmaker: So many trails to follow.

Archivist: Answers are scarce.

Filmmaker: That's what makes it a compelling story, even after all these years.

Archivist: And that radio show...

Filmmaker: I love that series from … What's his name? Edward Thomas?

Archivist: Thompson. Edward Thompson from the BBC.

Filmmaker: He got fired from the BBC for going down this rabbit hole night after night.

Archivist: He was quite a character from what I've heard.

Filmmaker: Definitely I have all the recordings and his notebook.

Archivist: Oh, really?

Filmmaker: In the end, Matteo Monti may have achieved what all artists aspire to. Immortality through mystery.

Archivist: Or perhaps the mystery is the art itself.

Filmmaker: A life shrouded in ambiguity.

Archivist: That's everyone's life when looked from the outside, when looking back by others.

Filmmaker: We all become phantoms, phantoms of ourselves, ghosts reappearing as fragments.

Archivist: Intriguing.

Filmmaker: I view what I do as a resurrection of sorts, crafting the very specific, almost ritualistic conditions that bring my audience into an enigma.

Archivist: Will you find an ending to this film of yours?

Filmmaker: An ending? What's that? The story lives on and on.

After the dialogue is over, the user will be presented with a screen containing a set of choices that will lead the user down varying paths that will keep evolving.

The process of writing Dialogue in the Dark

Okay, so what parts of that script did I write myself? What parts were written by AI? I’ll detail all that in an upcoming post.