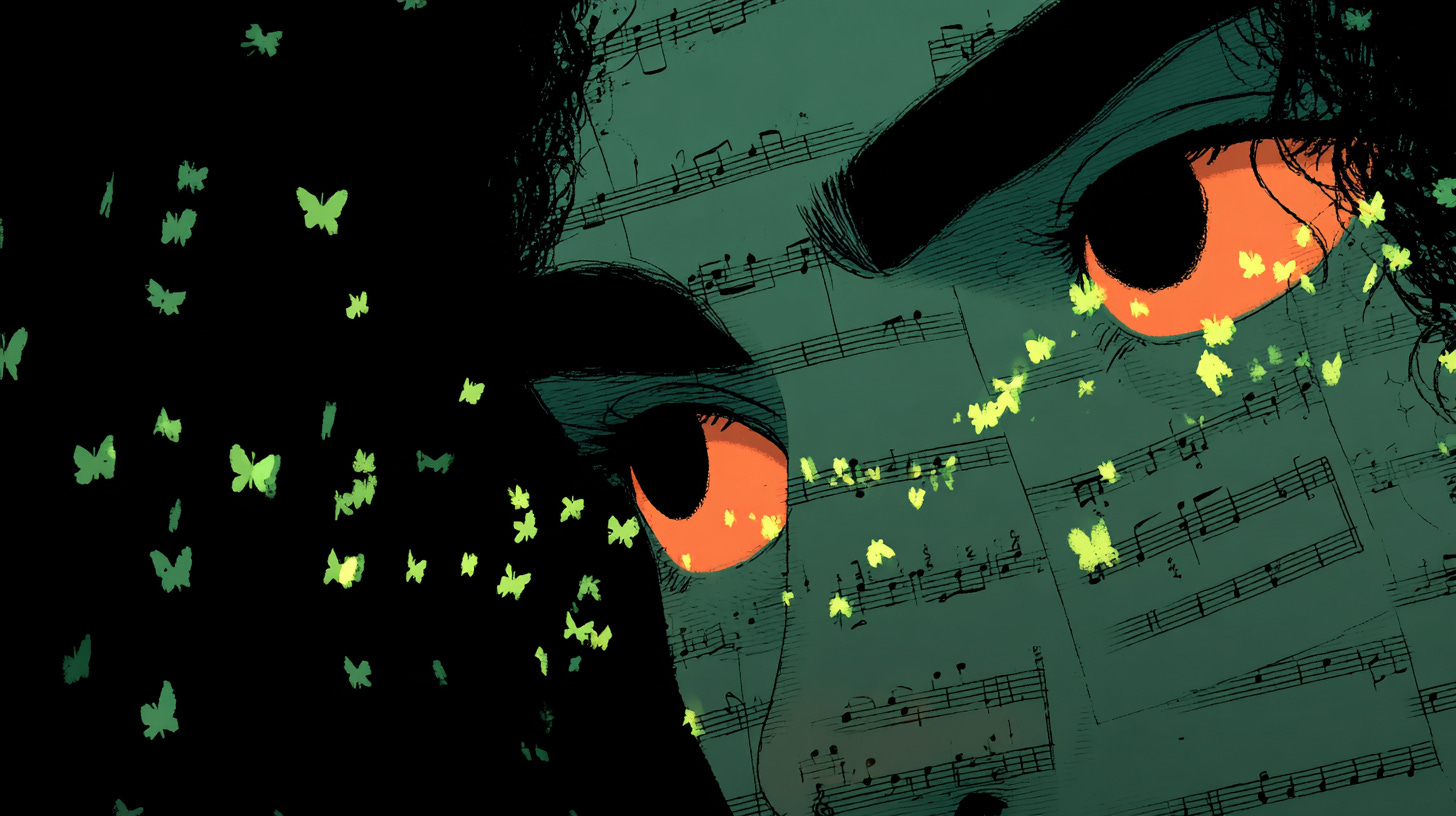

Music's Open Secret

What Generative Storytelling Can Learn from DAWs and VSTs

May 27, 2017: a Saturday night in the Flatbush neighborhood of Brooklyn. I was standing at the front of the stage in Kings Theatre waiting for the show to begin, the opening night for the North American tour of Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds. In casual pre-show banter with the chap next to me, I learned that he was a musician. Naturally, I asked, “What do you play?” He replied, “The laptop.”

At the time, I laughed, appreciating his playful reply, but looking back now, his words were more insightful than he probably intended. The laptop isn't merely the ubiquitous computer so many people use everyday. The laptop has become a versatile musical instrument through software generically known as Digital Audio Workstations (DAWs) that are powered by an ecosystem built around Virtual Studio Technology (VST).

Over the past three decades, these technologies have enabled musicians (from professionals scoring films to teenagers making beats in their bedrooms) to compose without physical instruments and, often, without knowledge of music theory. This ecosystem provides a powerful model for how generative storytelling, with its emerging AI-driven narratives, might build its own open framework, empowering visual storytellers to create interactive worlds.

Setting the Scene

A new genre of storytelling is evolving. Narratives are not limited to linear, predetermined outcomes. Instead, stories can adapt to real-time user interactions and algorithmic inputs. Generative storytelling is a process where AI algorithms help shape plot twists, dialogue, visual environments, and character behaviors.

Yet, as promising as generative storytelling appears, it faces a critical challenge: the absence of an open, interoperable ecosystem. Currently, creators navigating AI-driven narratives find themselves caught between competing proprietary platforms, each attempting to dominate the landscape and control the creative tools. Without open standards, storytellers risk vendor lock-in, limiting creative flexibility and collaboration. If generative storytelling is to realize its full potential, in the same way as digital music production, we must establish common technical standards and frameworks. This essay explores how the ecosystem around DAWs and VSTs overcame similar challenges, ultimately building an enduring and thriving creative environment that could guide the way forward for generative films, animations, and interactive narratives.

What the Digital Music Ecosystem Got Right

At the heart of digital music production is a powerful but straightforward concept: software-based tools that enable musicians to record, edit, mix, and produce complete musical compositions. The central software environment for this process is called a Digital Audio Workstation (DAW).

The choice of which DAW to use is a topic that elicits as much divergent opinion as politics and religion. Personally, I use FL Studio. My choice is not based on anything other than I really find the interface of FL Studio to be crisp and appealing. (Some other DAWs have UIs that feel very dated and give me eyestrain.) FL Studio’s UI is a place where I want to spend time.

I do most of my music sessions at night, when I’m relaxing after a day of coding and thinking about AI. As much as I personally like FL Studio’s interface, I’m sure there are others who hate it or dislike the workflow that FL Studio forces you into utilizing. But this essay is about DAW as software and not about which DAW to choose for yourself.

Earlier this year in my Responsible AI class, I raised the topic of DAWs. Only one student had heard of a DAW. It’s easy to forget that vibrant technologies exist that most people have never heard about.

DAWs have the capabilities of supporting specialized plug-ins known as Virtual Studio Technology (VST). VSTs are software-based musical instruments and audio effects (virtual pianos, synthesizers, drum machines, reverbs, compressors) that integrate with a DAW.

An excellent research-oriented overview of music production system, specifically the development of VSTs, is the 2025 paper: B. Andrei, M. V. Merino and I. Malavolta, "The Ecosystem of Open-Source Music Production Software – A Mining Study on the Development Practices of VST Plugins on GitHub"

Crucially, a VST operates as a standard developed by the Steinberg company in 1996, enabling interoperability: a VST created by one vendor can function inside any compatible DAW, regardless of who built it. (Steinberg has been a huge force in digital music production since the 1980s.)

Most VSTs are coded using JUCE, which is an open source application framework in C++. (For simplicity, I’m focusing on VST but there are other audio plugin formats.) This open plugin architecture means creators are not locked into a single vendor's ecosystem, fostering innovation, competition, and creative freedom.

But it’s not all roses and unicorns. A lot of virtual instruments are designed specifically for the Kontakt player, which is a product from the company Native Instruments. That company also has a very expensive suite of instruments and effects that are bundled into a set known as Komplete.

To understand what a thriving ecosystem might look like for generative storytelling, it's helpful to examine one of digital music’s most successful ecosystems: Native Instruments' Kontakt and its companion bundles known as Komplete. Kontakt, at its core, functions as a software environment within a DAW that manages a library of virtual instruments. Each virtual instrument replicates the sound and behaviors of real-world instruments such as pianos, violins, synthesizers, and drum kits, or creates entirely new sounds.

The advantage of Kontakt is its openness: third-party developers can build and distribute high-quality instruments that function seamlessly within the Kontakt player. For example, the acclaimed Noire piano, created by Galaxy Instruments in collaboration with Native Instruments, offers nuanced, expressive sound shaping controls accessible directly within Kontakt. Such collaborations allow small, specialized teams to leverage Kontakt’s infrastructure to reach audiences far beyond their individual capacities.

The Noire piano (retails for $149) sounds wonderful. Follow this link to hear the sounds and view some cool videos of how Noire was developed in collaboration with Nils Frahm: https://www.native-instruments.com/en/products/komplete/keys/noire

Native Instruments business models profits from this ecosystem through Komplete bundles: curated packages that group Kontakt-based instruments, effects, and sound libraries into cohesive collections. These are pricey. (Tip: Native Instrument regularly offers sales with deep discounts.)

Komplete serves as both entry point and creative powerhouse, attracting users ranging from hobbyist beat-makers to award-winning film composers. This carefully balanced ecosystem demonstrates how an open, standardized architecture combined with curated content can enable diverse creators to flourish and scale their creative ambitions far beyond the limits of a single vendor’s vision or toolset. Native Instruments also has a set of hardware that integrates with their musical plugins.

Just as I’m writing this post, Native Instruments released an 80-minute video on how to build an instrument for their Kontakt player.

Native Instruments is not without its share of people who detest the company, as any quick browsing of Reddit will reveal. There are many companies providing VSTs. Spitfire Audio is another that I often use. There’s also EastWest Sounds and an increasing number of subscription-based services like Splice. Plus, there are smaller sites like Mondo Loops offering sample packs, presets, and plugins.

Making music from samples is a small hobby of mine but I’ve already spent a significant amount of money on software, sound libraries, and gear. And that’s the point of this essay: there are business models that are built around creativity, business models that are built around offering tools that enhances one’s own creativity.

But, if you’re not familiar with this musical environment, you might be asking: is that really creativity? Here’s a take on opening up to the world of music composition from Guy Michelmore, who has one of the most informative and entertaining channels on music education. (The clip starts at the 20:30 mark. Watch the full video if you want a deeper overview of the latest editions of Komplete and Kontakt):

The reality of working with any of these tools by Native Instruments (or by competitors like EastWest Sounds) is that the learning curve is still significant compared to the ease of generating images and video with AI. With these enhanced tools in VSTs, you can create some pretty sounds with one finger. But it’s a very different effort to pull together a 4-minute song with layered instruments. Likewise, in Runway, you can easily create a 4-second video that is pretty cool. But pulling together a 4-minute film that conveys a story is a different level of creativity and self-expression.

At the 22:55 time mark in the above video, Guy Michelmore explains,

“There’s a continuum between originality and self-expression on one-side and painting-by-numbers on the other. And presets are definitely on the painting-by-numbers side. If you really want self-expression and originality, it comes from understanding what you’re playing…It’s the difference between going to a restaurant and making your own food…It’s not a path to self-expression and originality.”

Patterns & Techniques

The success of DAWs and VSTs is grounded on musical principles: scales, chord progressions, rhythmic patterns, and song structures. These foundational elements provide a universal language that plugins and DAWs can reliably build upon.

Similarly, visual storytelling and interactive narratives also rely on foundational narrative structures though stories lack the mathematical precision of music: the hero’s journey, three-act structure. Could these patterns serve as the universal frameworks necessary to establish an interoperable generative storytelling ecosystem? By learning how digital music harnessed these shared standards, we can better understand the potential for generative storytelling to similarly flourish.

“Listen I know it must sound absurd”

So, what does digital music production built on DAWs, VST plugins, open standards, and curated ecosystems offer as a lesson for generative storytelling? It demonstrates clearly how an open yet structured creative environment empowers innovation. In music, even dominant vendors like Steinberg and Native Instruments operate within ecosystems shaped by interoperability and agreed-upon standards. This openness has given creators at every skill level the ability to experiment freely, to mix and match tools, and to scale from casual experimentation to professional mastery.

Generative storytelling, whether through interactive films, animations, or branching narrative games, needs a similar foundation: technical standards to ensure compatibility, open marketplaces that encourage diversity of content, and flexible authoring environments that offer control without restricting creative possibilities. Imagine storytelling plugins as intuitive and interoperable as Kontakt instruments, AI tools as expressive as Noire’s generative note engine, and creative environments as engaging as your favorite DAW interface. If we get this right, creators won't just tell stories: they’ll orchestrate entire narrative experiences, shaping the future of storytelling itself.

“Listen I know it must sound absurd” is a line from this song recorded in 1984. Here’s a clip from that Nick Cave show in 2017 in Brooklyn.

I’m not visible but I’m in the crowd just beyond Nick’s right leg. I can tell you that the fabric of his pants is very nice.