One Story. Three Big Ideas. One Year.

My AI Focus for 2026

In life, you have to make choices. Not everything is equally important.

It’s easy to get distracted chasing the latest announcement, the newest AI model, the shiniest object. I’m not here to report AI news.

This year, I’m going all in on one project: creating an interactive story that lets me explore both the promise and the failure of generative AI for creativity.

The Story

Never Fear is my story about the absence of fathers and the obsessions their sons never name. In fact, I’ve already been working on this for 20 years. First as a novel, and now I’m adding new aspects as an interactive narrative. Maybe I’ll work on this for the next 20 years.

It spans three cities: Paris in the 1920s, Tokyo in the 1960s, Buenos Aires in the early 2000s. At its center is the artist Mateo Monti, who vanished from Paris in 1926. I wrote about the Paris portion of this story in October 2024 on this newsletter in a post titled "Crafting an Interactive Mystery”.

Are we uncovering the past, or rehearsing a story we want to believe?

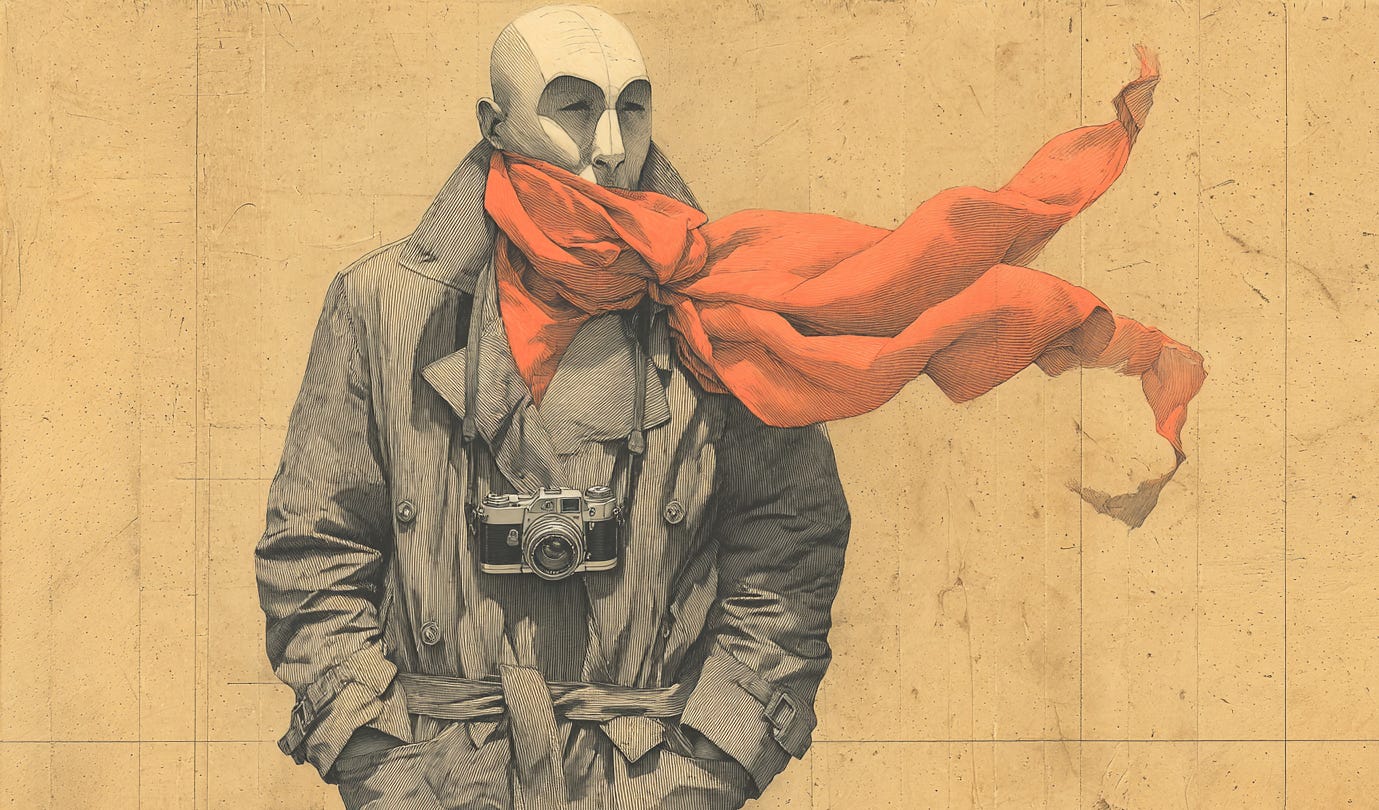

In 2026, I’m focused on the Tokyo chapter (Never Fear Tokyo). You play as Alejandro “Alex” Monti, an Argentine photographer who arrives in Tokyo to cover the 1964 Olympics. Beneath his assignment lies a personal mission: his father Mateo was sighted in Tokyo, decades after disappearing.

This isn’t just a mystery. It’s also an experiment in language learning: you and I are learning Japanese along with Alex as he learns. I’ll be using AI-generated voices as our guides through the story.

What I’m Actually Building

Let me be clear about what I’m trying to do. I don’t want to automate creativity. I want to learn how AI can help generate conditions that enable the audience to feel:

dread

recognition

obsession

tenderness

distortion.

These traits signal the absence of those you love. That matters to me.

So when I look at AI tools, I’m asking three questions:

Does this help me shape perception? I’m thinking about how the audience experiences something through attention, tone, uncertainty, and interpretation.

Does this help me maintain consistency across different media, different tools, different sessions?

What’s the actual workflow? Not for a 4 second clip, but the real process of making a complex story world.

Through this year, I’m documenting where AI helps and where it fails. Both matter.

Three Big Ideas

I’m organizing my work around three big ideas. Of course, these are not unique to me. These are concepts to explore.

I use the term big ideas, intentionally, based on the Understanding by Design framework for teaching. Throughout the year, I’ll break each one down into essential questions, learning objectives, and the practical skills and knowledge that emerge from the work.

Here’s the landscape:

1. Stylistic Consistency

Can AI generate coherent aesthetic identity across media?

For Never Fear Tokyo, I need grainy, 16mm-style visuals depicting rain-slick streets, flickering neon, figures appearing in photographs. I need period-accurate audio, e.g., jazz drifting through a bar.

For a chapter within the project, I need soundscapes, specifically whispers through walls in fragmented Japanese and Spanish, environmental sounds that shift, evoking voices from a future you’ll never see.

The challenge isn’t just generating these things. It’s generating them consistently. The same character aging across photographs. The same unsettling tone across audio scenes.

I’m watching developments in multimodal AI (models that work across text, image, audio, and video) because consistency across media is where so much falls apart right now.

2. Voice as Pedagogy

Can AI-generated voices that teach while they also tell a story?

Never Fear Tokyo isn’t just a mystery. It’s an experiment in language learning. You learn Japanese alongside Alex as he navigates Tokyo.

This is harder than it sounds. Voices for language learning need to be accurate; getting AI voices to pronounce Japanese correctly is not easy. Plus, the voices also need to be alive. A voice that teaches you to ask for directions needs different energy than a voice whispering through a séance. The same phrase repeated for shadowing (a language learning technique) shouldn’t sound robotic; it should have subtle variation, the way a patient teacher might say something three slightly different ways.

I’m building what I call the Japanese Sentence Studio as a tool for tracking generated performance variants. The same sentence, but with different emotional shadings. Hesitation. Confidence. The flattened affect of someone hiding something. (Maybe I’ll make the code for that tool available; I don’t know, yet. For me, it’s simply a tool to develop the project.)

The goal is to create AI-generated voices that feel like characters not language tapes.

Emi, your guide in Tokyo, should sound like a person with her own relationship to what she’s teaching you and not a disembodied pronunciation engine.

This is where AI voice generation gets interesting: not just mimicking human speech, but creating voices that serve both story and learning at the same time.

3. Context Engineering for Interactive Stories

What should an AI know, and when, to generate a meaningful experience?

Here’s the core challenge: what does an AI need to know to generate the next moment of your experience within an interactive story?

That’s context engineering: deciding what information to feed the system and when. For interactive fiction, this gets complicated fast. It needs a game engine.

I’m developing this in Unreal Engine because I don’t think any generative AI tool can maintain that level of knowledge about each player’s experience. To clarify: Unreal Engine is a game engine that handles many factors; there still need to be generative AI tools that handle other factors in the gameplay. (This is analogous to how you build an AI-enabled app by scaffolding a lot of Python code around an API to an LLM model, except in this case, the game engine is the app and code scaffolding.)

Unreal Engine is designed for tracking player state, managing persistent variables, handling branching logic, saving and loading progress. It’s a mature system built for complex interactive experiences, especially in 3D graphics.

AI tools, even with long context windows, don’t have the same capabilities for session persistence or player-state tracking.

Tools that simulate world models and generate video are good for prototyping and visualizing scenes. But they’re generative, not interactive in the game-engine sense, though there’s increasing interactivity. People are developing small game environments through world models. But these systems can’t track that you lingered on a photograph in session three and adjust how that photograph manifests in session seven. Or, at least, they cannot yet do that. I’ll be extensively using tools build around world models to test how far they can go in 2026. I expect there will be significant progress on world models and video generation by 2027.

The system needs to know the world: Tokyo in 1964, the visual language of the story, the mysterious woman who haunts these photographs, and other aspects of the storyworld. It needs to know the player: what they’ve noticed, what they’ve resisted, what patterns they’ve fallen into. And it needs to know the current moment: where we are in the narrative, what just happened, what’s possible next.

Context windows are getting longer. Memory systems are getting more sophisticated. But the real work isn’t technical, the real work is storytelling: deciding what should persist and what should fade. Or, if you’re coming from a game design background, the real work is in the gameplay.

Closing

I’m not trying to keep up with everything. I’m trying to go deep on one project and document what I learn.

These three big concepts—Stylistic Consistency, Voice as Pedagogy, Context Engineering for Interactive Storytelling—will organize the work that I release throughout this year. Each concept raises essential questions I don’t yet know how to answer. That’s the point.